The Dee - A matter of Time

During the following summer I received an art residency supported by the Farquharson family, which allowed me to spend several weeks to physically explore the Dee Catchment. During my time with the Dee River, I also began reading Alan Watts’ book Tao: The Watercourse Way. I was intrigued by the introduction to the book, which begins by stating: “The Tao is the way of man’s cooperation with the natural course of the natural world, its principles can be found in the flow patterns of water”. Philosophically, Alan Watts describes the essence of Tao as not being defined in words and as not being an idea or concept. “It may be attained but not seen… felt but not conceived, intuited but not categorised, divined but not explained. In a similar way, air and water cannot be cut or clutched, and their flow ceases when they are enclosed. There is no way of putting a stream in a bucket or the wind in a bag” (Watts, p. 42, (1)). This resonated with my exploration, because without the flow of water, there was no river. In a sense it felt my exploration was a study of flow. The more I experienced the multiple facets of rivers, it was the flow that formed the character of the waters.

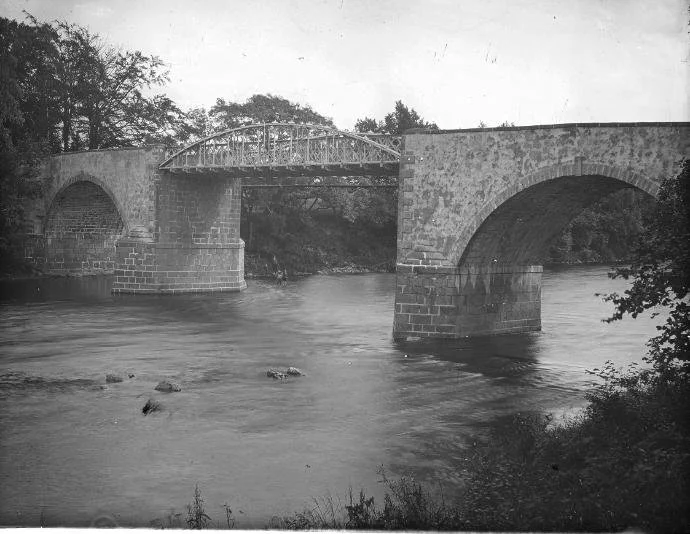

Spending time in the James Hutton Institute library, I learned that the beginnings of the Dee River would have begun during the melting of the last ice sheet which retreated and wasted away during the period between 16,000 and 13,500 years BP* (2). Before the birth of the Dee River, the waters of the Dee would have been locked away motionless in the solid volume of ice, waiting to melt and to begin the continual flow of the Dee River. Through all those thousands of years what would the flow of the Dee have experienced? What change has taken place along the banks of the Dee? I would have to begin a geological study to go back those thousands of years. However, while in the library of Aberdeen University, I became acquainted with George Washington Wilson’s early photographs of the Dee River, which were taken during his free time while being the photographer for the Royal Family during their visits to the Balmoral Estates. During the 1850s George Washington Wilson took many landscape photographs of the Dee River. These photographs took me back approximately 170 years. With George Washington Wilson’s black and white copies in hand, I followed some of these Deeside scenes.

It was virtually impossible to find the exact viewpoint that George Washington Wilson took his photographs. Most of the time the part of the bank where George Washington Wilson would have stood no longer existed and it was either presently part of the river bed or it was overgrown with trees and was not possible to find access to certain parts of the banks. Today, there are more trees along the banks of the Dee than there were 170 years ago. Taking photos from old bridges with active traffic proved too dangerous and my modern camera had a different focal length to George Washington Wilson’s camera, so it was never possible to find the same perspective even if I was standing at the same viewpoint.

Comparing these photos, gives me the impression that the Dee River, exists in its own time, where the river’s flow continues as before, the same yet somehow different to the flow of 170 years ago.

References:

1.Watts, A. (1975). Tao: The Watercourse Way. Souvenir Press, London, UK

2.Maizels, J. (1985). The physical background of the River Dee. Ed. D. Jenkins, In: The biology and management of the River Dee. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk, UK.

*BP is Before Present and also interpreted as Before Physics, which refers to the time before nuclear weapons testing artificially changed the proportion of carbon isotopes in the atmosphere. To account for this for radiocarbon calibration, BP begins at 1950.

George Washington Wilson photographs are copyright of University of Aberdeen

The accompanying colour photographs were taken during July 2019 and are copyright of Nicole AL Manley

The River Dee past and present

I wanted to understand more about the Dee River and it’s history in Aberdeen. Visiting the map library in Edinburgh, I learnt about the ‘Great Map’; a historical cartographic document that provided a graphic moment for Scotland when the landscape was beginning an era of rapid change. I compared a present day Ordnance Survey map of Aberdeen and traced out the city edge, the Dee River and the local tributaries of the Dee River. I then took the 1750 Roy map and scaled it to the Ordnance Survey Map and then traced out the city edge, and local rivers. Remarkably, the present day Dee River seems to retain a similar shape in comparison to 1750, but the smaller tributaries are unrecognisable. The tributaries within the agricultural areas bordering the city, had lost the winding form of small burns, and instead they have become re-routed to become the straight edges of fields, more similar to the shape of farm drains, instead of natural burns. The burns that existed outside of Aberdeen in 1750 are not present in the Ordnance Survey map and the present tributaries that enter the city disappear under the city. It is surprising that all the small tributaries entering the Dee during 1750 have disappeared and there are culverted burns, such as Denburn and Gilcomston Burn that go under the city. Disappearing or hidden rivers are common in cities in the UK, like for example the lost rivers described by Paul Talling’s book “London’s Lost Rivers (1), which were all culverted and covered to continue their course underground. When is a river no longer a river and becomes a culvert or a drain? Is it when the river goes into the dark and looses all contact with sunlight and this is the moment it disappears? Why can we not live with rivers in our cities, when we rely on water everyday?

References:

Talking, P. (2011) London’s Lost Rivers: A walkers Guide. Random House Books, London, UK

Nicole AL Manley (2021) Sketch of the River Dee and tributaries as shown in the Roy Map (1750) and present day Ordnance Survey Map (2016)